RELATED TOPICS:

- What Is Blast-Phase MPN? How Progression Turns MPN Into Leukemia

- Genetic Changes That Drive MPN Progression: From JAK2 to High-Risk Mutations

- Chromosomal Damage and Chromothripsis: When Genetic Chaos Accelerates MPN

- Why MPN Treatments Stop Working as the Disease Progresses

WHY MYELOPROLIFERATIVE NEOPLASMS PROGRESS

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) often behave like slow-moving blood cancers, but they are biologically unstable. Over time, genetic damage, chronic inflammation, and changes in the bone marrow can allow the disease to become more aggressive. This progression may lead to advanced myelofibrosis, an accelerated phase, or blast-phase MPN, which behaves like leukemia. Understanding why MPNs progress helps patients and doctors recognize risk earlier and guides future treatment strategies.

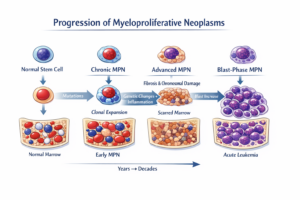

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are chronic blood cancers that arise from abnormal blood-forming stem cells in the bone marrow. For many patients, MPNs remain stable for long periods and can be managed with monitoring and treatment. For others, the disease evolves into a more aggressive form, progressing to advanced myelofibrosis, an accelerated phase, or blast-phase MPN, a leukemia-like condition with a very poor prognosis.

MPN progression is not random. It reflects a long biological process driven by genetic evolution, chronic inflammation, and bone marrow damage that unfolds over many years.

MPNs Begin Long Before Diagnosis

Genetic studies show that the earliest mutation leading to MPN often occurs decades before diagnosis, sometimes in childhood or even before birth. These early mutations most commonly affect JAK2, CALR, or MPL, genes that regulate blood cell growth.

At first, the mutated stem cell behaves almost normally. Over time, it gains a competitive advantage, gradually producing more blood cells than healthy stem cells. Diagnosis usually occurs only after blood counts rise enough to cause symptoms or complications, meaning the disease has already been evolving silently for years.

Early Driver Mutations Do Not Explain Progression

While JAK2, CALR, and MPL mutations initiate MPN, they do not fully explain why some patients progress and others do not. Many individuals with high levels of these mutations remain in chronic-phase disease for decades.

Progression occurs when MPN cells acquire additional mutations in genes involved in DNA repair, epigenetic regulation, transcription, and cell division. These secondary changes allow certain subclones to survive better, divide faster, or resist treatment. This process is known as clonal evolution, and it is a central mechanism of MPN progression.

Genetic Instability Accelerates Disease

As MPN cells continue dividing, they accumulate DNA damage. In advanced disease, this damage often appears as chromosomal abnormalities, which are uncommon in early MPN but frequent in accelerated and blast-phase MPN disease.

Some patients experience catastrophic genetic events in which chromosomes break and are reassembled incorrectly, dramatically altering cancer cell behavior. Once this level of genomic instability is reached, the disease often becomes aggressive, treatment-resistant, and prone to leukemic transformation.

The Bone Marrow Environment Plays a Critical Role

MPN progression is not driven by cancer cells alone. The bone marrow microenvironment changes alongside the disease. Abnormal blood cells release inflammatory signals that activate surrounding stromal cells, immune cells, and blood vessel cells.

This chronic inflammatory state leads to bone marrow fibrosis, a scarring process that disrupts normal blood production. Fibrosis further weakens healthy stem cells and favors malignant clones, creating a vicious cycle that accelerates progression.

Importantly, inflammation in MPN is driven not only by cancer cells but also by non-malignant cells, making it a systemic disease process rather than a purely genetic one.

Progression Often Occurs in Stages

MPN progression frequently unfolds in stages rather than as a sudden transformation. Patients may progress from essential thrombocythemia or polycythemia vera to secondary myelofibrosis Others enter an accelerated phase, marked by rising numbers of immature blood cells called blasts.

When blasts exceed a critical threshold, the disease is classified as blast-phase MPN, which behaves similarly to acute myeloid leukemia and carries a median survival measured in months.

These stages reflect increasing genetic damage, worsening marrow failure, and loss of normal cell regulation.

Chronic Inflammation Drives Further Damage

Inflammation is not merely a symptom of MPN — it actively drives progression. Inflammatory cytokines increase oxidative stress, damaging DNA and promoting new mutations. Inflammation also enhances survival signaling pathways, allowing malignant cells to outcompete healthy ones.

Specific inflammatory markers have been linked to a higher risk of progression to blast-phase disease, regardless of MPN subtype, helping explain why symptom burden often worsens as disease advances.

Age and Overall Health Matter

MPNs are most commonly diagnosed later in life, and aging itself increases progression risk. Aging is associated with baseline inflammation, reduced DNA repair capacity, and altered immune surveillance, all of which favor clonal expansion.

Other health conditions may further contribute by increasing systemic inflammation or stressing organs already affected by MPN, indirectly accelerating disease evolution in some patients.

Why Progression Can Feel Sudden

Although progression may appear abrupt, the underlying biological changes usually develop over many years. Much of this evolution occurs at a molecular level long before changes appear in blood counts or symptoms.

By the time progression becomes clinically obvious, genetic and inflammatory damage has often reached an advanced stage. This is why modern MPN management increasingly emphasizes long-term trends, molecular testing, and bone marrow evaluation rather than isolated lab results.

Why Understanding Progression Matters

Understanding why MPNs progress reframes the disease as a dynamic, evolving condition rather than a static diagnosis. This knowledge supports earlier risk identification, improved monitoring strategies, and the development of therapies aimed at slowing or preventing progression rather than reacting after transformation occurs.

Scientific Sources (Open-Access / PubMed)

-

Williams et al., 2020. Evolution of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms from Normal Blood Stem Cells.

Explores early mutation acquisition and long latency before diagnosis. -

Grinfeld et al., 2018. Classification and Personalized Prognosis in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms.

Describes clonal evolution and genetic risk stratification. -

Tefferi & Pardanani, 2019. Blast-Phase Myeloproliferative Neoplasm: Contemporary Review.

Reviews outcomes, biology, and treatment challenges of blast-phase disease. -

Mesa et al., 2020. Accelerated Phase of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms.

Defines accelerated phase and its prognostic significance. -

Chatain et al., 2021. Inflammation and Fibrosis in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms.

Details inflammatory drivers of fibrosis and progression.